If we take the history of the portrait painting from "parsuna" till the age of Romanticism as a gradual evolution towards cognition of a personal value of a human being, as a history of distracting of "myself" from "we", we can draw a succession from "parsuna" through the whole XVIII century to the romantic portrait as: life - life-story - biography - fate (G.V.Vdovin's idea). Provincial portraits of the nobles easily find the right place in this succession somewhere between life-story and biography, while the merchants' portraits somehow combine the characteristics of life and narrative guidelines from "Domostroy" or "Yunosti chestnoye zertsalo".

A new genre of literature - a "merchant's life-story" - emerged along with the development of the merchants' portraiture: "…Ivan Mikhailovich with all his passion dedicated himself to the virtuous life; he began to live his life in praying, fasting, labour, vigil, self-restrictions, spoke little, avoided leisure, exercised in reading Gospels and the Bible, every day attended the public sermons <…> He hated luxury,…preferred moderation and simplicity and an old fashion in clothes, furnishing, carriages, etc. <…> Especially he was an enemy of all civic entertainment and never allowed his family-members to attend any kind of those disgraceful events: either sledding in winter or walking in the public garden, to say nothing of the theatre" (P.Polidorov, "Ivan Mikhailovich Nemytov"). This quotation could be considered as a kind of an ideal merchant's portrait, or, to be more precise, as its verbal equivalent.

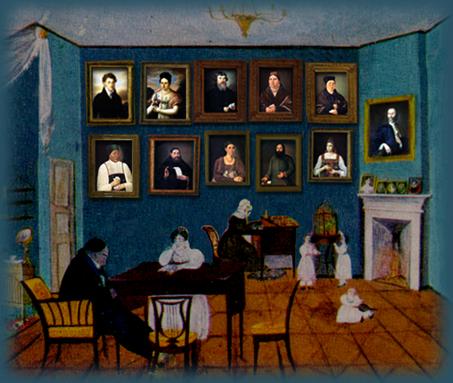

From this point of view the merchants' portraits are closer to parsuna than its predecessors -the noble portraits of the XVIII century. Static postures, emphasised serenity of the faces, inner reservation and closure create a special feeling of time. There's neither static past, nor foreseen future, but an ever-lasting present.

The merchants' portraiture has been formed as a particular artistic phenomenon by the end of the XVIII century and ended up in 1860-ies. The main reason for its rapid fading away was fast dissolving and vanishing of the main customers of this very special type of art-works in the post-reform Russia. Tretyakovs, Morozovs and Mamontovs - people, who required totally different art, replaced Kusovs and Rakhmanovs.